Carnegie Dunfermline Trust | Carnegie Hero Fund Trust

Your Trustees of Carnegie Dunfermline and Hero Fund Trusts

Letters to Andrew Carnegie | Carnegie Dunfermline Trust | Carnegie Hero Fund Trust

Dear Mr. Carnegie,

“To bring more of sweetness and light; that the child of my native town, looking back in after years will feel that … life has been made happier and better. If this be the fruit of your labours you will have succeeded; if not you will have failed.”

You wrote these words 116 years ago in your letter from Skibo, founding our Trust, and in this year of the centenary of your death, we will now attempt to reply, laying out how we have indeed tried to succeed.

There cannot be many trusts and foundations which received such clear guidelines as those contained in your three-page letter to us, or many that would turn so willingly to the words of their founder for their current reference points. Yet so it is in our case. Your letter told us to experiment, to be pioneers, to not be afraid of making mistakes, and, in that staggeringly forward-looking and trusting statement, to “try many things freely, but discard just as freely.”

How right you were. Needs change, social mores change, and economic environments fluctuate. But poverty is still with us, children still need opportunity and encouragement, older populations face social disconnection, and environmental choices impact on us all.

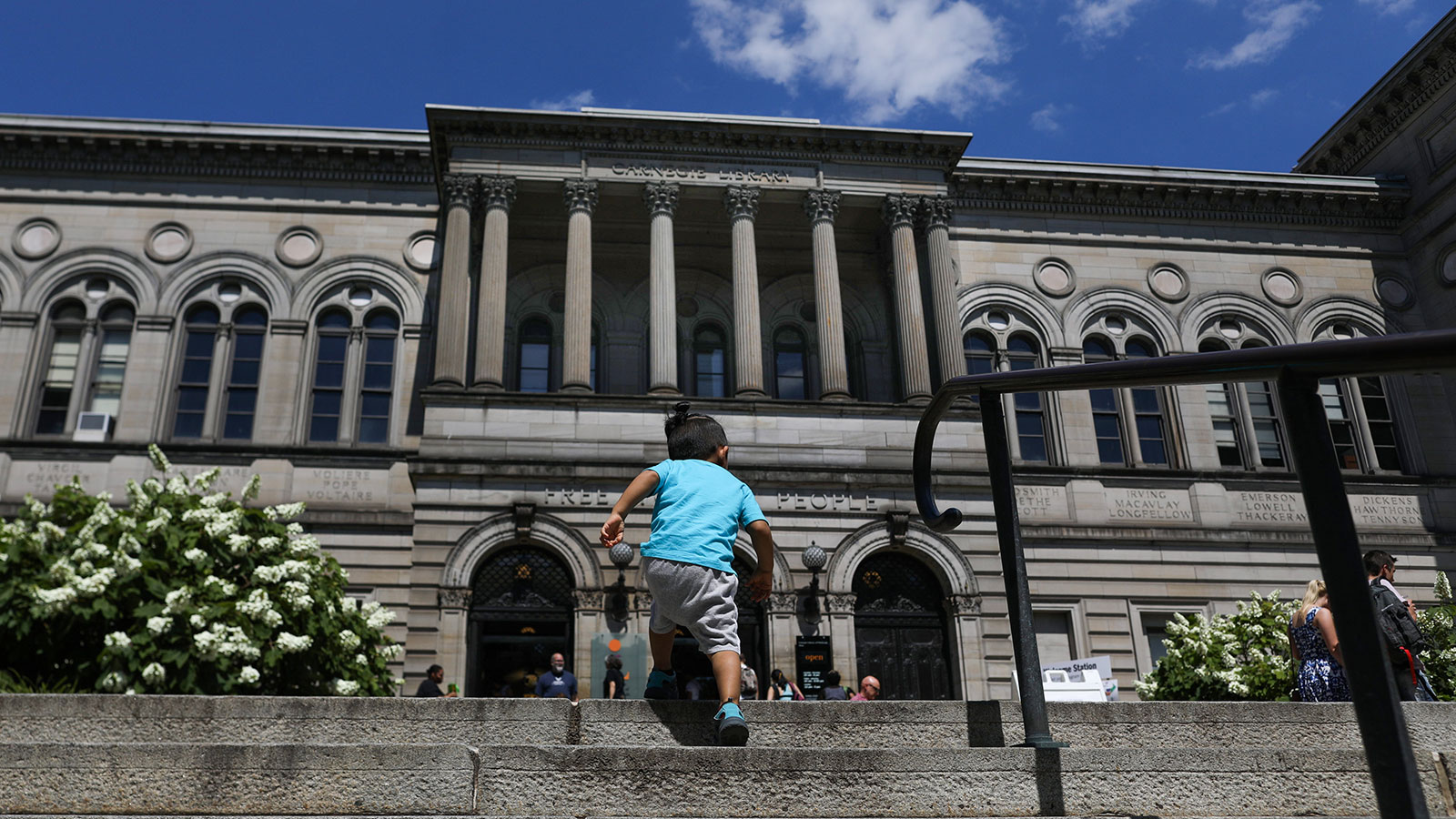

When we started out, we followed your lead in providing buildings (your name still remains synonymous with libraries). We bought and built children’s clinics, children’s homes, swimming baths, institutes for both men and women, and recreational, sports, crafts, music, and drama facilities for all. But buildings are costly to run and, with the introduction of national health and welfare services in the UK at the end of the 1940s, our ownership of these buildings ceased. Instead, we have moved into direct grant giving, facilitation, partnership projects, and an ethos of punching above our weight. We use your name to engage interest and commitment in pursuit of common agendas based, as ever, on the fundamental principles of need. We hope you would approve.

We have also taken liberties with the interpretation of the “child of your native town.” Greater inclusion and shifting educational and economic boundaries have broadened our reach, whilst we still give something special to your local child. In the last couple of years alone there has been a 55% increase in assisting disadvantaged school children, and a growing total of over 4,000 pupils a year enabled to participate in sport. True to “trying many things freely,” we support pilot and start-up projects in the hope they will grow and flourish, but not conditional on success as a prerequisite for support.

Also in your all-encompassing letter, you identified Pittencrieff Park as fundamental to our organization’s existence. Your pride in its purchase, and our subsequent stewardship, have been constants in our identity. Your wish to see experimentation and development of this magnificent and historic urban green space has led to controversy, debate, financial challenges, and, ultimately, the encapsulation of what green spaces in an urban environment represent. I believe you would appreciate the passion that the park has engendered and perhaps some of the irony that, whilst in 1904 Patrick Geddes’ ambitious proposals for the park were rejected by trustees, they are now seen as innovative and relevant, and they form the basis of international study. By degrees, we are working towards your goal of a recreation space for the people. The Glen Pavilion, new café, and fully inclusive play parks, together with all the open spaces, are nationally recognised and fully used and appreciated all year round. The mansion house, with its double link to Pittsburgh through yourself and John Forbes, is now in the spotlight of opportunity.

In 1908, you added the British-based Hero Fund to our responsibilities. In contrast to our more local work, the Hero Fund takes us across the whole of the UK, Ireland, and Channel Isles. You said the Hero Fund movement was your “ain bairn” (own child), something special and personal to your beliefs. You had already founded the Hero Fund Commission in Pittsburgh, but only we started with a beautifully inscribed Roll of Honour, which today bears moving witness to the nearly 7,000 individuals recognised. Sadly, the majority of these inscriptions are posthumous and, whilst the nature of incidents has changed somewhat with the times, the consistent element of selfless humanity remains throughout. The ongoing support provided to families through the Hero Fund has meant that contact has been maintained, in some cases, for over sixty years — a practice we are proud to continue.

During your lifetime, your wife, Louise, had purchased the cottage in Dunfermline where you were born, to ensure the preservation of its significance. After 1919, she provided the funding to build the art deco hall which, together with the cottage, now make up the Andrew Carnegie Birthplace Museum. Like you, she did not hesitate in her belief that our trustees would manage this area of work, completing our tripartite responsibilities that continue today.

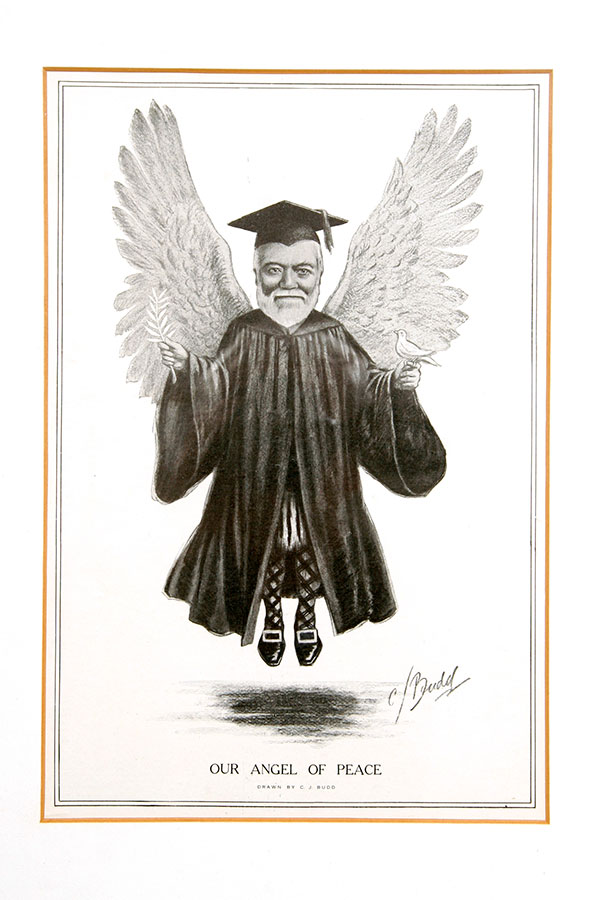

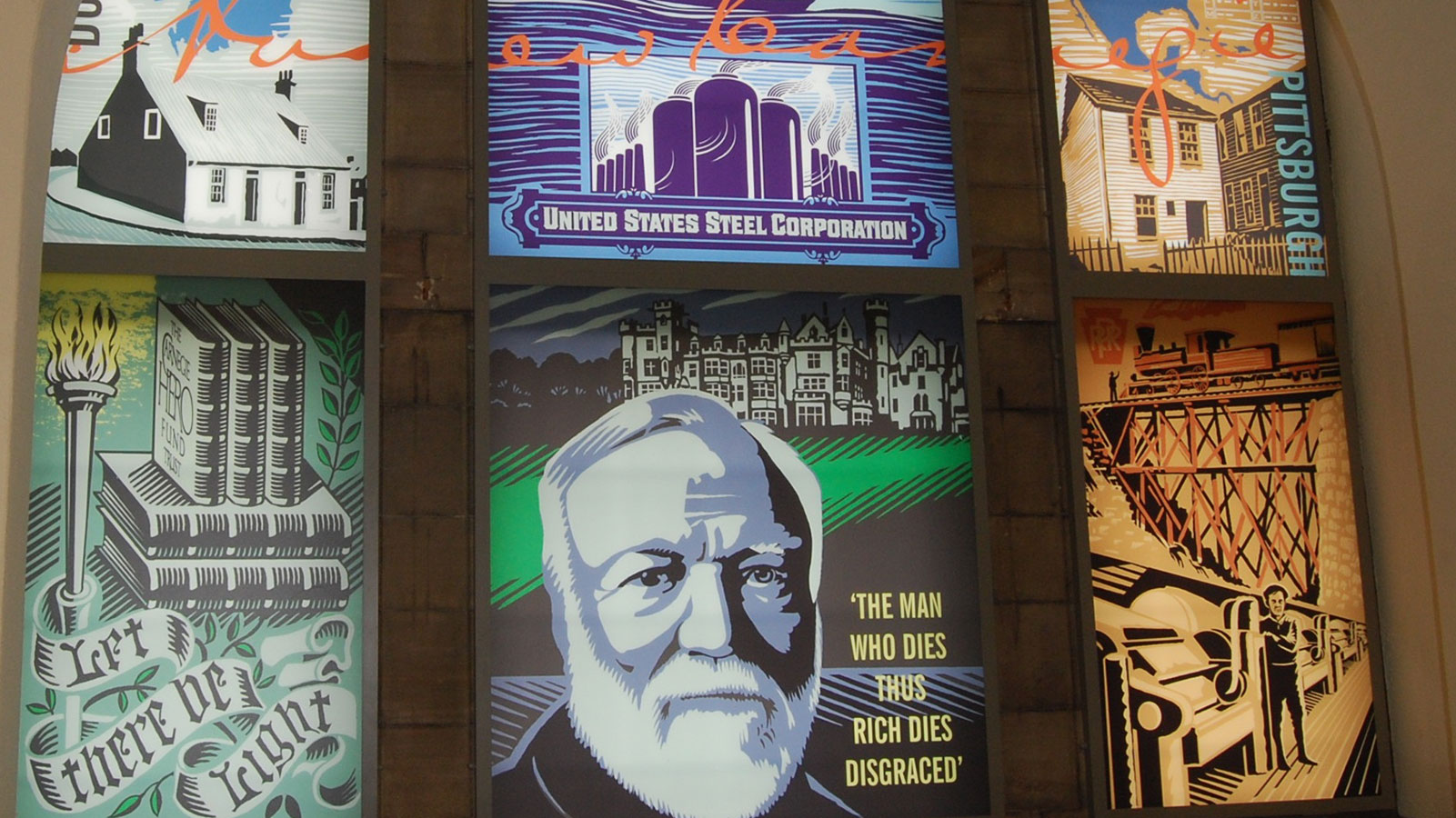

Louise wanted us to tell your story, providing an example of what success can look like, as well as the impact of your international philanthropy, and how others might be encouraged to follow in your footsteps. For some decades we did not value the role of the museum and its potential worldwide voice as we might have, but the establishment of the Carnegie Medal of Philanthropy changed all of that. The greater awareness of the combined voice of all the Carnegie institutions has prompted the museum to revisit the ways in which it tells your story. Your valuing of education, peace, science, entrepreneurship, economic development, and so much more is now conveyed in ways relevant to all ages. Perhaps most significant of all is your living, breathing, and influential philanthropic legacy, one hundred years after your death.

You once said, “There is little success where there is little laughter.” Fun and interactive engagement are powerful tools for sharing timeless messages and fresh ideas. As part of the many events of this centenary, your diplodocus replica from London journeyed to Glasgow, providing us with a topical and humorous platform to illustrate so much of your legacy — the shared assembling of a bright red Dippy the Dinosaur in the Birthplace Museum from over 35,000 pieces of Lego. We are certain you would have enjoyed being part of this collective design challenge.

Finally, toward the end of your life, you commissioned a beautiful window from Tiffany Studios in New York as a memorial to your family, to be installed in Dunfermline’s historic Abbey. Your reaction when the Abbey authorities rejected the window as not being religious enough was not recorded, but the window then embarked on an eventful and itinerant life, being stored for some years under your baths in Dunfermline, then in the new Carnegie Hall, and, finally, here in our headquarters when they were built in 2007. In what seems a most fitting end to the first centenary of your legacy and the beginning of the next, your wishes were fulfilled in August 2019, when the window was installed

in the location you chose.

Have we succeeded? Maybe not always in the ways you anticipated or the ways we would have wished; but we have tried, and, in your own words, we hope you will be “well assured” that we will continue to try to the best of our ability.

Your Trustees of Carnegie Dunfermline and Hero Fund Trusts

Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh

Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland

Carnegie Institution for Science

Carnegie Foundation | Peace Palace

Carnegie Rescuers Foundation (Switzerland)

Fondazione Carnegie per gli Atti di Eroismo

Stichting Carnegie Heldenfonds

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Carnegie Corporation of New York

Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs