Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching

Anthony S. Bryk

President

Letters to Andrew Carnegie | Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching

Dear Mr. Carnegie,

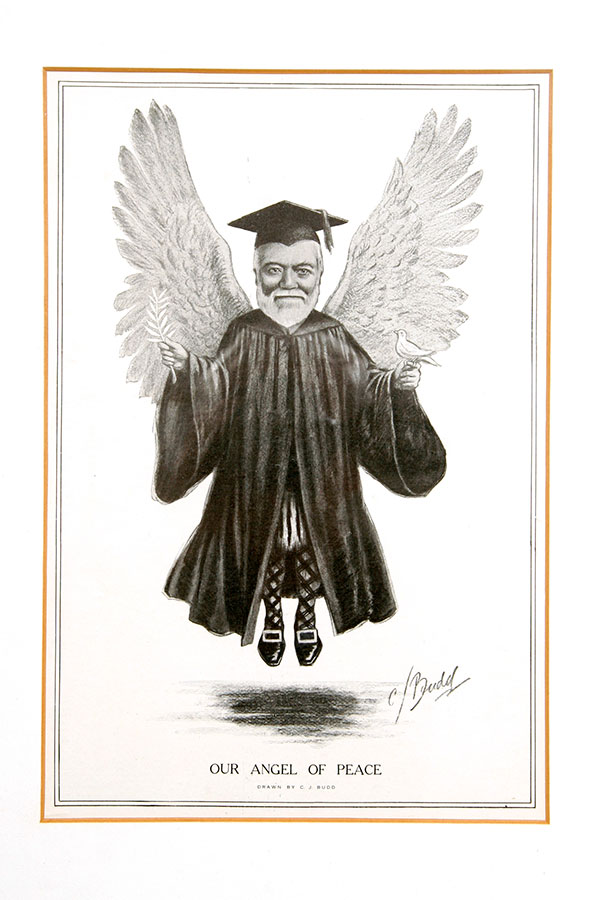

On this, the 100th anniversary of your passing, I am honored, as the ninth President of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, to take a moment to reflect upon your legacy and impact in the field of education and to ruminate on the challenges that still lie ahead.

It is with a sense of awe and humility that I approach this task, recalling the words of Nicholas Murray Butler, former President of Columbia University, on what would have been your 100th birthday: “What greater responsibility could any one of us bear than to have been asked by him, or by those whom he asked, to assume a share in the conservation of these forces which he set in motion, in their direction and guidance for human betterment through the next generation?” We are not stewards simply of the funds, but also of the ideals, and it is the ideals that continuously inspire and challenge us.

First and foremost, Mr. Carnegie, I continue to be inspired by your belief that teaching can and should be a dignified profession. You founded the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching with the specific goal, as stated in our charter by the United States Congress, to “encourage, uphold and dignify the profession of the teacher.” Since its inception, the Foundation has kept this value in mind, manifesting it in our work to elevate standards for higher education, strengthen preparation for the profession, honor the scholarship of teaching, and, in the Foundation’s current work, bring teachers and researchers into more productive collaborations to address longstanding inequities in educational outcomes from pre-K to post-secondary.

Theirs is most noble work: to inspire, to shape, and to help each child have a meaningful personal life and become a productive contributor to that ongoing great experiment of democracy in America.

Secondly, you believed strongly in the innate capability of persons and the capacity of institutions to learn and to improve. The Foundation has spent the majority of its more than 100 years convening leaders across the education landscape with the aim of making our educational institutions more efficient, more effective, and more student-centered. From the Flexner Report, to the recommendations from the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education, to the establishment of the Carnegie Classifications, to our current work on using improvement science principles and organizing improvement networks, there is a long history at the Foundation of convening educational leaders around improving our educational institutions.

Lastly and most importantly, Mr. Carnegie, I continue to be inspired by your belief in the power of education to transform lives. In “The Gospel of Wealth,” you recall with “devotional gratitude” how Colonel James Anderson of Allegheny would open his library to the children of Pittsburgh. You, your brother, and Henry Phipps would attend every Saturday to exchange books. You never forgot this example of openness and generosity, and you believed that one of the best uses of your wealth was to fund universities, libraries, museums, and parks — palaces for the people, where anyone can have access to the knowledge, beauty, creativity, and noble spirit contained within these open spaces. You considered it your duty, even a privilege, to gift educational institutions to communities around the world, and these communities continue to reap the benefits. You recognized that a productive and convivial democratic society rests on the education of its citizens. Unless more had access to the kinds of learning opportunities that had been afforded you, a free, civil, and open society could not endure.

Having grown up in a blue-collar working-class family, the only child on either side of my family to attend college, I know personally the power of education — the intellectual world that it opens as well as the social and economic opportunities that it affords. Having worked in the field of education for over forty years, I have seen again and again how education can ennoble and enrich students’ lives, but I have also seen how quality education continues to be denied to far too many of our nation’s children.

So yes, Mr. Carnegie, having access to institutions of knowledge and culture not only brings value into our own lives, it also strengthens the social fabric of our communities. But today we need to do more than just create access. Our aspirations for our education system have increased dramatically over the past four decades. We now aspire to achieve quality educational outcomes for every child. We use these words so effortlessly now — every student succeeds — that we can easily underappreciate how ambitious these goals really are. Never before have we challenged educational systems in this way.

We often hear stories like yours and mine, where people of modest means succeed through some combination of family support, intellect, grit, and, often, that special teacher who touched their lives. But we should not let our personal accounts blind us to the great tragedy of the countless numbers of children who continue to be denied opportunity for a better life by virtue of the community they may have been born into or their family life circumstances. We must expect more from our education systems.

In order to achieve the ambitious goals that we now hold, to educate every child well, we need to work in very different ways. This may well sound strange to you, Mr. Carnegie, as Frederick Taylor was a contemporary of yours and greatly influenced the evolution of the industrial workplace, including your steel mills. As significant as his ideas were in fueling the industrial revolution, the seeds of great human debasement were also embedded within them. Taylor assumed that he knew best how to organize work, and that laborers should simply follow his directions. Workers were, in essence, replaceable parts. He wanted their labor, not their minds; nor did he attend much to their dignity as human persons. It took W. Edwards Deming, some forty years later, to challenge this thinking. Deming argued that if all you ask of your workers is their labor, your organization is throwing away 90 percent of its social intelligence for problem solving. Deming’s insights are especially important now, as the educative tasks in our schools and colleges have become more complex, and the organization necessary to carry out this work more complex as well. To reach a new effectiveness frontier requires a social organization well beyond the mechanical formulations of an earlier era. Moreover, we live in a time of extraordinary, sustained, and rapid change. Our educational institutions not only need to get better, they need to learn how to continue to get better, as our society will continue to demand even more changes over the years ahead.

Education today is a vast institutional enterprise involving millions of educators and over 100,000 different contexts in which students regularly interact with teachers around subject matter. Making every one of those contexts work every day for every teacher and child is a daunting task. Moreover, there is no simple “new idea” waiting in the wings to solve this problem. The solution won’t be found in just adopting some new curriculum, or adding another program or some new web-based apps, regardless of how promising any of these might be. In truth, these are all just parts, albeit potentially valuable parts, but their power remains inert unless we focus on how these various parts become more productively integrated into the fabric of our educational organizations. In short, we confront a systems improvement problem. How can we get our educational institutions to work better and more reliably every day for every child in every context in which students are educated? There is no deus ex machina to save us. Rather, we need to roll up our sleeves and take up the sustained and sometimes tedious tasks of continuously improving how our educational institutions can create more value reliably for all who walk through their doors every day.

Today we confront a growing chasm between rising aspirations as to what we want from our schools, and what they can routinely accomplish. Realistically, we have no strategy to achieve our rising aspirations, whether it be all children reading by grade 3, all children career and college ready by the end of high school, or all new teachers succeeding in educating their students.

Comprehending this reality demands a fundamental shift in how we think and act toward educational systems improvement. Much practical learning occurs every day as people engage in their work. Numerous fields have become much more productive by acknowledging this natural inclination to learn by doing, and then building on it in deliberate, systematic ways. Moreover, the problems we now seek to solve are too complex to lend themselves to broad-based solutions by individuals or institutions working in isolation. Rather, we need to join in deliberately structured improvement networks that attend to practical problem solving.

This means getting down into the micro details of how our educational systems actually work, and how any proposed set of changes is supposed to lead to improved outcomes. It means using evidence to guide the development, revision, and continued fine-tuning of how tools, processes, work roles, and relationships might better interact to produce the outcomes we seek.

In addition, it is important, but not sufficient, to know that something can work (i.e., what we now call “evidence-based” and store in the What Works Clearinghouse). We also need to build the practical know-how necessary to generate quality outcomes reliably under diverse and different conditions. This means paying explicit attention to variability in performance, and questioning what works for whom and under what set of conditions.

In the past, we have relied on a select group of people to design interventions and establish policies, and then those actually doing the work — teachers, principals, and education leaders — are cast as followers of these directives. In contrast, effective organizations today, across many different sectors, draw on W. Edwards Deming’s insights and actively engage those involved in the work who are central to its improvement.

Rather than assume that some external experts already know the answer to improving schools, we need to listen to what students, teachers, and their families are experiencing and how they are making sense of the social world in which they live. We need to understand better what is and is not working for them and why this may be so. As Danielle Allen reminds us in her book, Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality, respect for the voice of others — the right to be heard — is the most basic expression of the concept of equality. So it is incumbent on those who have power to use their power to truly listen to the voices of those we seek to engage, who are most dependent on our good efforts for their success.

As large and complex as this problem is, I am also convinced that we can learn better and faster. Most recently, I saw this in action at our sixth annual Summit on Improvement in Education. Over 1,700 people from around the country and around the globe gathered together for three days of workshops, presentations, and conversations, all aiming to improve educational effectiveness and reduce inequities in educational outcomes. It was a thrilling event where participants felt inspired, empowered, and enabled to make a difference in their local contexts. I think you would have been proud to have this event carry your name; proud that more than 100 years after your passing, thousands of educators were working together to dignify the profession of teaching, to make schools and colleges more effective, and to make progress toward our aim of educating well every child.

So here in the twenty-first century, we continue to be enlivened by and to advance upon your inspiration to do all things that encourage, uphold, and dignify the profession of teaching and to improve the institutions where it occurs. Theirs is most noble work: to inspire, to shape, and to help each child have a meaningful personal life and become a productive contributor to that ongoing great experiment of democracy in America.

In closing, I thank you for your great gifts, Mr. Carnegie. Both the investments themselves and the spirit with which those gifts were given continue to inspire and challenge all of us who are charged to be good stewards to your legacy.

Sincerely,

Anthony S. Bryk

President

Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh

Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland

Carnegie Institution for Science

Carnegie Foundation | Peace Palace

Carnegie Dunfermline Trust | Carnegie Hero Fund Trust

Carnegie Rescuers Foundation (Switzerland)

Fondazione Carnegie per gli Atti di Eroismo

Stichting Carnegie Heldenfonds

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Carnegie Corporation of New York

Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs